Introduction

One way to make sense of our experiences, the reasons behind certain behaviours and incidents, is to write them down as a story. Asides from being helpful for the writer for seeing the connections between certain life-events, these can all be used in advocacy or peer support in order to share an encouraging and helpful message.

In this chapter, we will give you some tools and ideas about how to put your own story into words and how to use that story to encourage, inspire and support others. This, in particular, can be quite challenging, as it does require you to process and share parts of your life that you may not have shared before.

3.1 What is a recovery story?

A recovery story is a tale of the storyteller’s own personal struggles and, more importantly, of how they have managed to overcome them or how they learned to cope with remaining issues. Recovery stories are widely used in therapy and 12-step programs to help people work through and reflect upon the events in their life that have caused them pain and the effect that they’ve had on their development.

The length and the contents of a recovery story largely depend on its purpose. If it is a tool for the person themselves to reminisce and see how much they’ve grown, it can be as long and elaborate as the person wishes. Such a story would go into detail about certain memories or give just the outline of what the person’s been through. When the recovery story is meant to be shared with others (a so-called public recovery story), its structure, range and wording have an importance. In this case, the recovery story is meant to leave the listener with a sense of hope, a useful bit of information or a message for them to consider. These public recovery stories focus more on the positive recovery part of our journeys to encourage others to find the information and help they might need.

The most important question in this chapter is the following: what is the message you would like others to take from your story?

3.2 How to know if I am ready to write and/or share my recovery story?

In theory, opening up a word document or finding some paper and a pen to write about the difficulties you’ve been through may seem like an easy task, but in reality it’s often rather complicated. Personal thoughts, feelings and actions are particularly hard to put down in words, even moreso, when you’re attempting to write about the hardest moments in your life.

The questions you could ask yourself to affirm whether you are ready to compose your recovery story are these:

- Have you reached the point where thinking about the struggles you’re addressing no longer brings you strong negative emotions?

- Do you believe in your recovery?

If you’ve answered “no” to either of those questions, writing your experience story may not be the best exercise for you at this time. The danger in attempting to compile your story before you have reached the point where these memories have stopped causing you pain is in the possibility of getting stuck in the feelings accompanying your experiences. When these feelings are still unprocessed and not enough time has passed from the events that you would like to share in your story, it is easy to get trapped in the anger, distress and hopelessness that you may have felt then and it can be tough to return to the present moment. In case you do try to write your experience story and find yourself reliving the struggles you’ve been through, it’s best to set it aside for the time being and focus on the things, people and activities that are currently accessible to you or that make you feel better.

Remember that your readiness to share your story may always be changing and growing. For every possibility to share, check in with yourself as a first step. Ask yourself the two previous questions and take a look at your overall well-being (you can also find useful material for this in chapter 8: Self-care). Sharing your experience always opens the door to some vulnerability. For example, people may react to your story in unexpected ways and comment or ask about difficult topics. Answering those questions is much easier in a good headspace.

3.3 How to write a personal recovery story?

In order to help you structure your recovery story, we have three exercises that highlight various aspects of your experiences and offer ways to form a cohesive and refined story around your recovery. It would be best to do the exercises in the order in which they are presented and to take ample time to relax and really focus on them.

Exercise 1

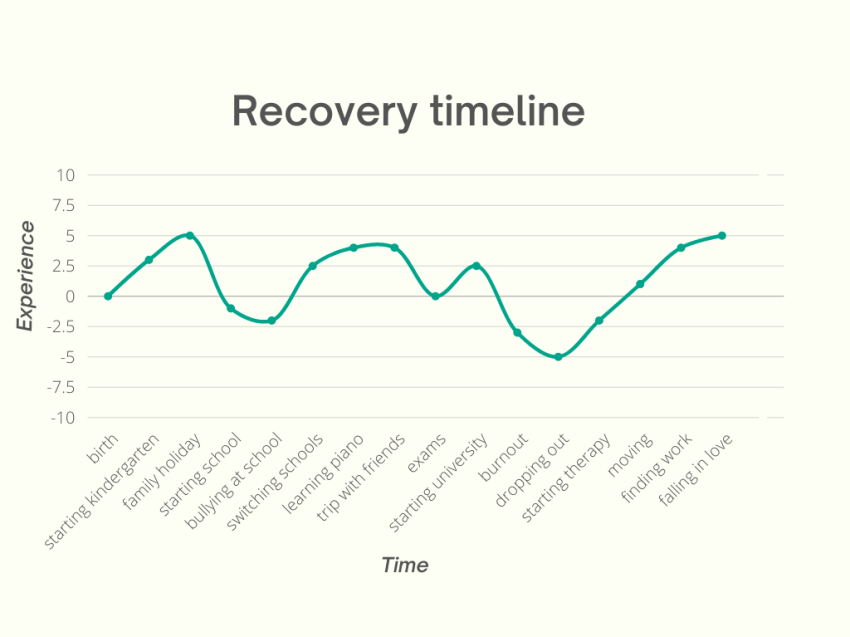

Perhaps the easiest way to tell a story is to start from the beginning and go from there. In this exercise you have the chance to create your own timeline with both the positive and negative events that have impacted your life. A graph like the one shown here is one of the easiest ways of recounting all the different turning points and assessing in what order they took place and how they affected you. After drawing up your own recovery timeline, you can pen down the first draft of a story, using the turning points to make a rough outline and filling it in.

It’s usually most convenient to use a pencil and paper for this exercise, but if you wish, you can use our template on Canva (link).

Exercise 2

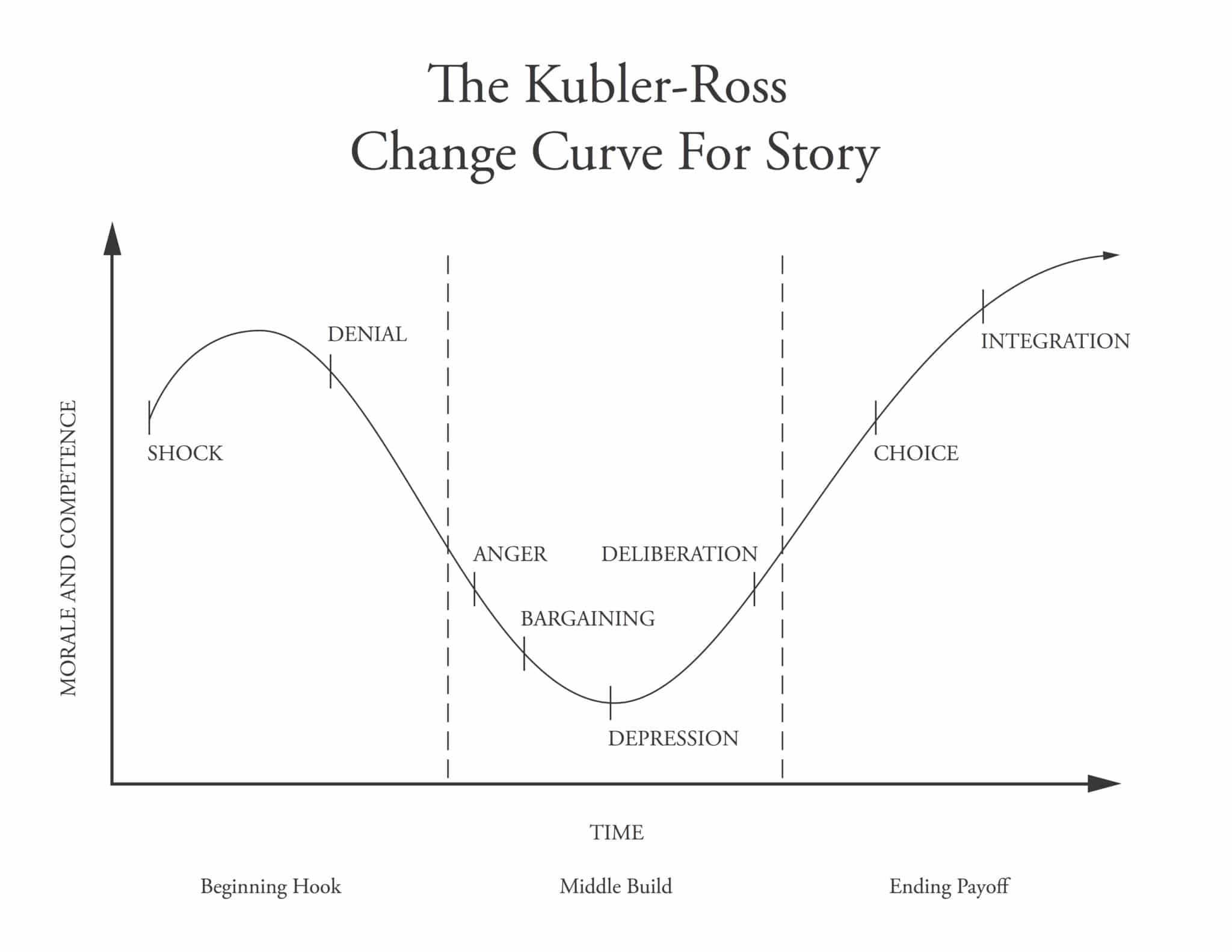

After completing the first exercise, it’s possible to pinpoint the roughest periods in your lifetime and with this exercise, we are diving deeper into the difficulties themselves and the journey of recovery. This can be especially useful, if you want to concentrate on a more or less clear-cut crisis. Even those with more complex struggles can benefit from this method, as they can analyze the different stages of their crises.

As a framework for reference, we turn to a psychological model that Elizabeth Kübler-Ross has developed to explain the stages of going through extreme changes. Adapting this to a recovery story, there are some additional points that you could deliberate: are there other points you would add to your crisis curve? Were there any points when you experienced confusion, uncertainty, helplessness or numbness? Was your recovery aided by acceptance, outside help, learning or experimentation? Are there any new skills, ideas or confidence that you gained from emerging from this crisis?

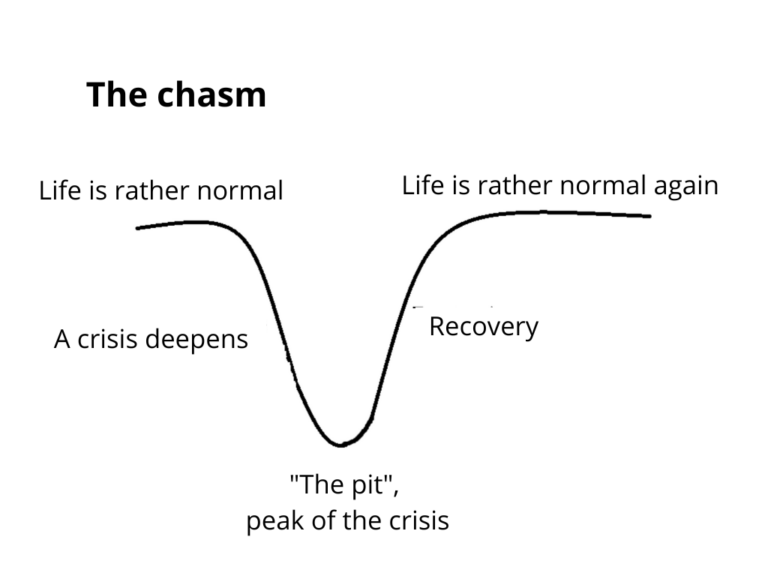

Here is another, more minimalistic graph that may support you in this exercise:

Exercise 3

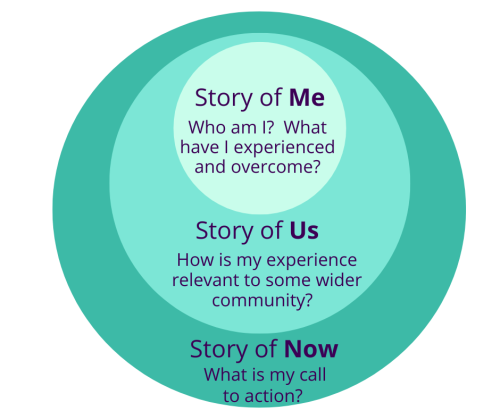

The third exercise is inspired by Marshall Ganz and his three-fold public narrative structure called Story of Self—Story of Us—Story of Now. (source)

This three-fold structure can be especially beneficial for those situations, in which we are sharing our recovery stories with a wider audience (rather than one-on-one settings) – for example at a mental health awareness event, workshop or while sharing our stories in a video or writing.

Before starting this exercise, please think of an imaginary audience that you would like to share your story with, an audience that you would like to give some hope and encouragement to. Are they peers – people experiencing similar problems as yours – or perhaps their friends, parents, partners? What age group do you feel the most connected with? Or perhaps you would like to aim your story towards teachers, social workers or other professionals that could benefit from hearing your lived experience to bring more awareness to their work? Of course, you can craft many stories for many audiences from your experiences, but choose one group for this exercise.

The third exercise consists of three parts (elements) that are shown on the image.

The first element – “Story of Me” can be a compact version of the stories that you have written down during the last two exercises. It usually starts with some introduction of ourselves, and it tells the story of what I have experienced and what I have discovered through that process. As this is an exercise of writing a public recovery story – meant to be shared – a majority of the story should focus on “the way back up” on the previous graphs: the people, actions, thoughts and support that has helped you recover. As a rule of thumb – aim for at least half of the ‘Story of Me’ to be focused on recovery.

For this exercise, try to pick out the most important points that you want to share from the previous exercises. You may ask – how do I know what’s important? For ourselves, understandably, all of the choice points are important, as they are a part of our life and identity. But think of it this way – what definitely needs to be told for the story to make sense and to be understood? There are often some points that can be left untold or only briefly mentioned, whilst still keeping the story “complete” for the listener.

The second element – “Story of Us” is the part of the story in which you make a connection to some wider community. Most often it can be the peers in a similar situation. It tells how your story – your experience, situation, struggles, values – relate to a bigger “us”. Ganz reminds us that we participate in many us’s: family, community, faith, organisation, profession, nation, or movement – and the story of us expresses the values, the experiences, shared by the us we hope to connect to at the time.

In this part of the story, you can tell about your motivation: why you want to share your experiences. Quite often, it is because we have discovered that there are people like us – people who may feel support from hearing that they are not alone in their experiences. Here is your chance to address them, to let them know that you know they exist. It can be as simple as it gets, along the lines of “I know that there are people who are feeling similar to the way I was,” – just expressed with sincere words that feel yours.

The third element – “Story of Now” is the part where you make a clear point or a call to action and provide a hopeful perspective. Here is your chance to tell your listeners what they can do to make a difference. You can think – what would you wish to say, especially to those who feel a great connection to the “us” that you’ve outlined in the last element. It is a chance to articulate the moral of the story, or moreso, the key points that you wish to pass on.

Now we welcome you to take some time and write down your own story in this three-part structure. Don’t worry if it doesn’t feel perfect, or nowhere near it. Your recovery story is always growing and changing! In one sense – you keep growing and changing and so does your story. And secondly – your story tends to change a bit with every telling and with every audience.

If you would like to see an example of a recovery story using this structure, check here:

3.4 What to say and what not to say in a recovery story?

Congratulations! You have now written down the first drafts of your very own recovery story. Well done! Probably some questions popped up while writing: should I write about some topic or not? Is that appropriate? What words should I use? This is very normal in this process. There are some aspects to keep in mind when preparing a story for sharing with an audience.

What are some things that definitely should be in a recovery story and why?

- DO describe feelings, thought patterns or worldview that you experienced while you were having difficult times. That is especially beneficial for two important kinds of listeners:

- For peers with a similar experience, this often gives a message of “You are not the only person feeling this way. You are not alone.”

- For people who haven’t experienced something similar, it gives a valuable insight for understanding these struggles.

- DO talk about how you decided to change the situation or start looking for help. This gives encouragement and can give practical ideas about taking the first steps towards recovery.

- DO share who and what supports, inspires and helps you – both in the beginning of your recovery and now, as you are telling the story. This can give beneficial ideas for people, who are currently struggling or in the process of recovery, as well as to people who are supporting someone else in their life.

Short exercise 1

Write down 5 things that have helped you in your journey.

- DO aim for the majority of the story to focus on recovery (not the struggles) and ALWAYS end your story on a positive note. It is easy to focus on describing the tough times, but remember that the recovery story is meant to leave the listener with a sense of hope. As we invite our listeners on a journey about difficult topics, we also need to help them switch to an optimistic mindspace (or at least neutral one). Ending on the positive gives a good feeling both to the storyteller and the public.

Short exercise 2

Write down 2 possible ways to conclude your recovery story in a positive and encouraging way.

It can be a combination of a positive look back (e.g. “I’m really glad that I survived that period in my life”, “I’m so grateful that I told someone about my problem”, “I’m happy that I have friends that supported me”) and why you chose to share your story (e.g “I wanted to share my story with you in the hope that I can encourage at least someone to seek help earlier than I did”).

What are the things that should not be shared in a recovery story and why?

- AVOID descriptions of harming yourself. It sadly can be picked up as a “tip”, as something to try – even if you don’t mean to present it like that. So therefore, don’t give detailed accounts on:

- how you have injured or harmed yourself,

- how have you made suicide attempts,

- how have you engaged in behaviours of disordered eating,

- how have you hidden self-harming behaviours from other people.

Most importantly – even if you are asked about these details, you should not share them. You can say that it would not be wise to share that information.

- DON’T provide points for comparison, especially regarding disordered eating and addictive behaviours. It happens easily, as we want to show how bad the situation was, and numbers are an easy way. But it can unfortunately lead people into comparing their experience with yours and also to decide that their situation is not severe enough to seek help. It is important to avoid mentions of:

- weight,

- calories (either in limits or amounts consumed),

- exact amounts of daily hours or money dedicated to problematic behaviour (e.g exercising, gambling)

- amounts of food eaten etc.

- DON’T share your recovery story on substance addiction as a part of prevention work (meaning – don’t share it to people who are not dealing with substance abuse or addiction). This can have the opposite results. If your recovery story is centred around overcoming addiction, then you have to be very attentive with choosing your audience and choose not to share that story at schools or in places where the audience is not fully made up of people in recovery from an addiction.

If substances have a role in your recovery story and the story would not make sense without mentioning the topic, mention them briefly and neutrally (e.g “I drank a lot of alcohol in that period and it worsened my problems”, “I was abusing substances and that probably triggered the psychosis”). If you need to mention them, then:

- Don’t use slang or specific drug names. Stick to most neutral terms (“alcohol”, “substances”).

- Don’t frame using them in a problem-solving manner (e.g “I was feeling very bad, so I started drinking”)

- Don’t describe the feelings that you felt while under the influence (e.g “I had never felt such euphoria”)

- Don’t mention the amounts or frequency that you were using the substances.

All of the previous points may sadly act as an encouragement or a challenge to try them. ‘

- DON’T give detailed descriptions of common triggers – any kind of violence or abuse, accidents, traumatic events. If they have a role in your story, be mindful of the people listening to you – probably some of them have experienced it themselves. To take care of their wellbeing, give a warning beforehand. In the story, mention the topics as briefly and neutrally as possible.

3.5 Adapting your story to different audiences

In telling recovery stories to the public, we need to always keep in mind the people that we are talking to. To adapt your story for telling to different audiences, it is useful to focus on two points:

- the vocabulary – the words we use

- the topics – what are we talking about

When preparing to share your story, think about the audience that you are talking to. How old are they? What’s their experience in life? Are they members of some profession (e.g teachers, social workers, doctors)? What may be especially useful for them?

If you don’t know some important aspects about your audience (i.e age, their previous contact with the topic), then definitely find out beforehand so you can best adapt your story for telling it to them.

Regarding adapting the vocabulary, the main question is “is it understandable?”. You usually can’t go wrong with using simple words. They can be understood for most audiences with ease and very little adaptation is needed.

“Simple is best” is especially the case for when we are talking to adolescents, young people or people with learning difficulties. If we are very literate in some topics, we often tend to use complicated or very specific words. Sometimes we don’t even notice it! Try to be mindful of that and check if your story has words that are not commonly known for the audience. If you need to use them, explain them as soon as you mention them.

For example, when a university student is telling their story to their peers, they can of course talk about the struggles with writing their ‘Bachelor’s thesis’ and be understood rather precisely. But when the same student is telling the story to youngsters in basic school, it’s probably much more useful to talk about struggles with a ‘big important paper for the university’ or even simply ‘schoolwork’.

For adapting the topics, the main questions are “is it understandable?” and “is it relatable?”. So firstly, are we talking about things that they are equipped to understand, and secondly, can they relate to my story in some way? Even if the experiences themselves are different, quite often the struggles are related to problems or values that are common to most people – relationships, motivation, self-worth, acceptance, etc. Try to emphasise those aspects!

In this, it’s good to use a bit of imagination and try to see the world through their eyes. What would be most helpful and interesting to them? For talking to peers, it’s often the coping methods that have helped us. For talking to parents, teachers or other people working as supporters, it’s often how to notice problems and how to offer support. Generally, the topic that is most relevant to someone is the topic that they can use in their daily lives.

Exercise

- Write an experience story you could share to a group of 15-year olds.

- Then think what you would change if you were instead telling it to their parents.